By Carla AbouZahr, CRVS Country Adviser, Vital Strategies/Bloomberg Philanthropies Data for Health Initiative; Martin W. Bratschi, Deputy Director, Technical Implementation, CRVS Improvement and Dr. Philip Setel, Vice President, Civil Registration and Vital Statistics, on behalf of the COVID-19 and Civil Registration discussion group*

As of June 17, 445,380 lives in 188 countries and territories had been lost to confirmed COVID-19. The question is, how many more have succumbed to this deadly pandemic without our knowledge?

The daily death toll represents a key marker of the COVID-19 pandemic, alongside updated numbers of confirmed cases and hospitalizations. But relying on these figures alone can lead to an underappreciation of the scale and direction of the epidemic— as they do not systematically include people who have died outside of a hospital setting (e.g., at home or in a social institution such as a nursing home) and because of limited testing and challenges in attributing cause of death.

Most governments already have a resource where they can find the data they need to better capture COVID-19’s true impact, and to implement lifesaving policies: civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) systems.

National CRVS systems are designed to capture all vital events (including births and deaths) within their borders, including detailed information on all deaths broken down by age, date, location and cause. At Vital Strategies, we work with governments around the world to ensure that everyone is counted and that high-quality data are available to policymakers. Now, we’re working alongside partners to tap into CRVS systems as a core tool for monitoring and calibrating a country’s COVID-19 response.

Monitoring the Pandemic with CRVS Data

In response to the urgent need for timely data to track the pandemic, many countries are using their civil registration systems to monitor “excess mortality,” or the gap between the total number deaths (from all causes) and the historically expected levels of mortality for the same place and time of year. Excess mortality can be monitored both nationally and sub-nationally (e.g., in cities), providing a greater degree of granularity than national-level data alone. The concept of excess mortality has been used to study regional differences in deaths due to heatwaves or during unusually cold winters.

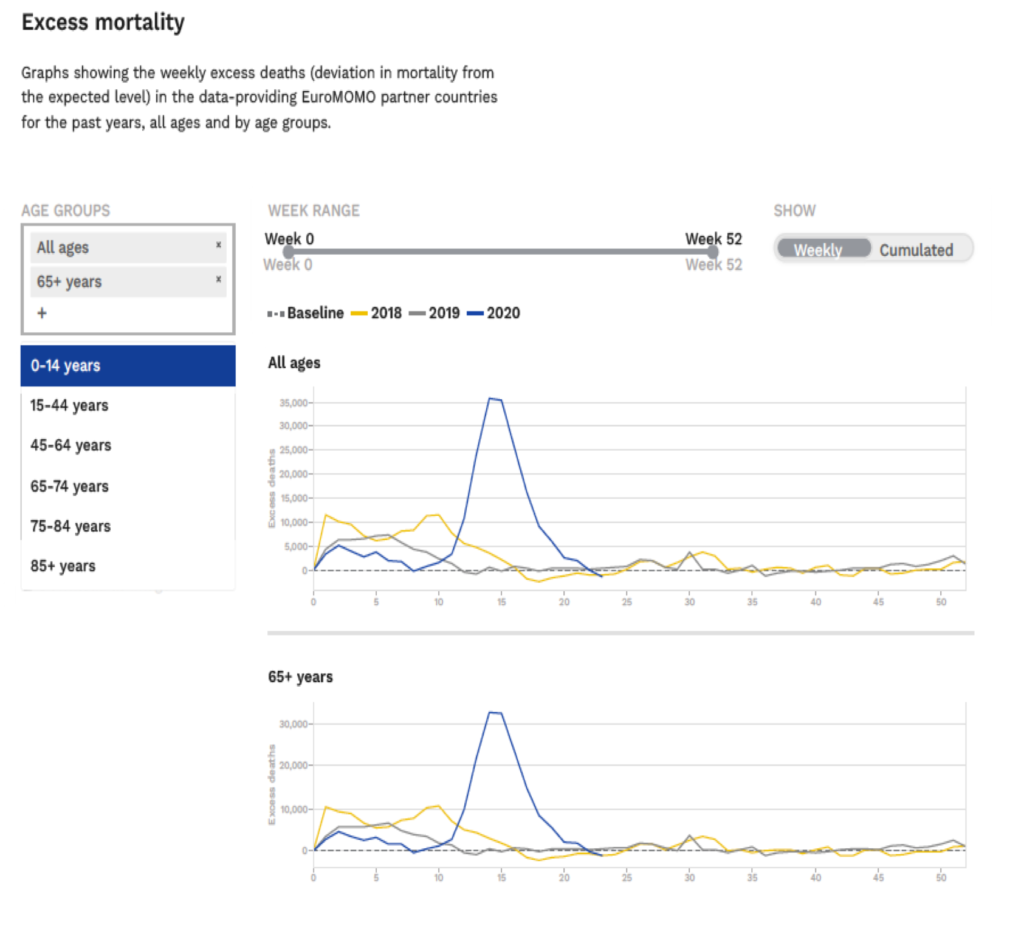

Weekly reports of excess death could provide the most objective way of assessing the scale of the COVID-19 pandemic and identifying lessons to be learned. Excess mortality estimates reported by 24 countries participating in the EuroMOMO network show striking increases in total deaths during the first 16 weeks of 2020 compared with the same timeframe in 2018 and 2019, coinciding with the current COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1). This near real-time information provides valuable insight into the scale and direction of the pandemic.

Whereas high-income countries are able to publish excess mortality data from their CRVS system with a turnaround time of one to two weeks, many low- and lower-middle income countries cannot produce data as quickly. In this case, a rapid mortality surveillance system may be established to monitor total deaths in a network of carefully selected sentinel sites, such as hospitals, that have a high probability of seeing cases and can report on death data on a regular basis. Rapid mortality surveillance can either leverage existing CRVS systems or be absorbed into them to maximize the likelihood of long-term success and improve the notification and ultimate civil registration of deaths everywhere.

Access the new guidance from Vital Strategies: Revealing the Toll of COVID-19: A Technical Package for Rapid Mortality Surveillance and Epidemic Response

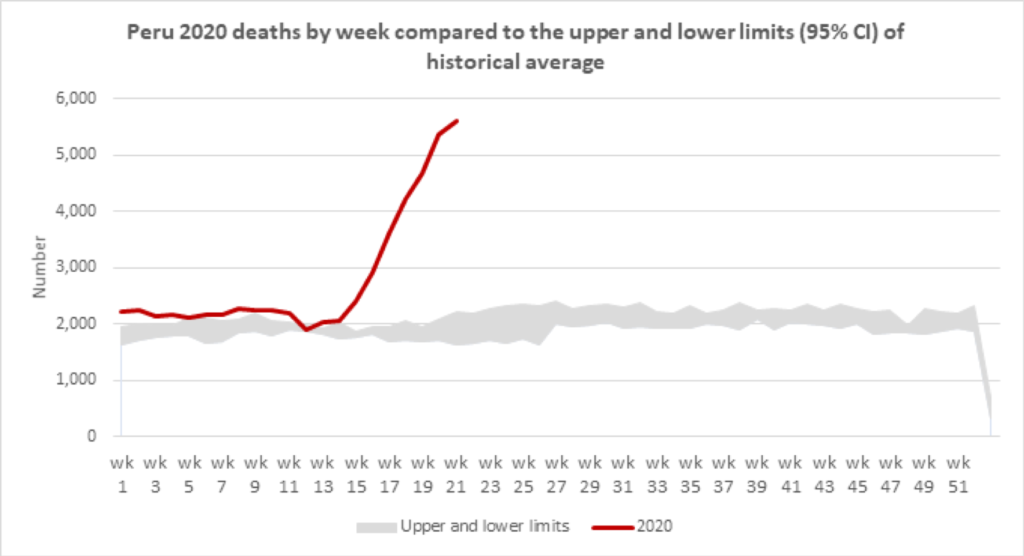

Several countries within the Bloomberg Philanthropies Data for Health Initiative have begun using existing CRVS systems for rapid mortality surveillance. For example, data from the Peruvian Ministry of Health’s automated system for cause-of-death assignment and mortality registration illustrate the trajectory of the country’s epidemic compared to the historic average (Figure 2).

Peru: Number of deaths with online death certificates per week, 2020

By analyzing excess mortality data by age, sex and location, governments can identify potential areas and population groups at higher risk. This includes older adults, people with noncommunicable diseases and communities exposed to socioeconomic hardship, especially when localized to specific geographic areas—such as the surge in COVID-19 cases in Singapore among previously untested migrant laborers.

Rapid surveillance of mortality also accounts for deaths indirectly caused by COVID-19. Reports have surfaced of deaths linked to social isolation during periods of restrictive physical distancing measures, such as suicide, interpersonal violence within the home, or reluctance to seek medical care for fear of becoming infected.

In New Zealand, where civil registration is available online, death notifications are being used to track COVID-19 mortality on a daily basis. This information is disseminated within hours; Registrar-General Jeff Montgomery explained to Vital Strategies’ CRVS team how this allows the COVID-19 response team to monitor death rates and make real-time decisions on when to increase (or decrease) the government’s level of response. In the U.S. state of Hawaii, an electronic death registration can link the cause of death listed on a person’s death certificate to laboratory testing results. According to Alvin Onaka, State Registrar, this has greatly improved both the speed and accuracy of information on causes of death, especially mortality related to COVID-19.

Maintaining CRVS Services During the Emergency Response

Continuous monitoring of vital events based on civil registration provides important epidemiological evidence needed for pandemic response, but current restrictions on movement and limitations in nonessential services can risk impeding the timely civil registration of events. The United Kingdom, for example,halted registration of births and marriages, and allowed for registration of stillbirths and deaths only by telephone. India has not declared civil registration an essential service during the country’s COVID-19 emergency response and registrations of births and deaths have come to a halt even in urban areas.

Recording complete information on a death takes time, to allow for data compilation, quality assurance and analysis. In the context of COVID-19, measures being taken to manage the pandemic can cause undue delays. For example, overwhelmed medical professionals must digest new WHO guidance on completing medical certificates of cause of death. Delays are also expected for the reporting of deaths occurring outside of hospitals, given that attending doctors normally responsible for completing death certificates may be self-isolating, unwell or under pressure to attend to patients in strained health care systems.

The U.N. Statistics Commission has requested member states to assess the extent of COVID-19-related disruptions to civil registration and report on experiences and efforts to maintain services. Initial responses show that many countries are reporting closures of civil registration offices due to “stay at home” orders and restrictions in service delivery. Even when facilities remain open for civil registration services, there are reports of significantly reduced demand for birth and death registration on the part of the population due to movement restrictions and fear of becoming infected.

Protecting CRVS Services

CRVS systems play a critical role in people’s lives—from improving access to health care and education, to the guaranteeing the right to vote, and ultimately to furnishing data critical for policymaking in health and other sectors. During the COVID-19 crisis, CRVS functions must be able to continue uninterrupted. Difficulties in accessing civil registration services and delays associated with national and local lockdowns will make it harder for people to obtain the legal documents they need, such as birth, death and marriage certificates. There are risks that vital events may remain unregistered even after the pandemic, with people facing increased difficulties in accessing services to which they are entitled, such as health care, child benefits, or identity documents.

The completeness, timeliness and reliability of vital statistics—especially mortality statistics—will be compromised at a time of amplified need for these data. Births and deaths excluded from the system are most likely to come from the poorest and most disadvantaged populations. It’s also possible the momentum gained strengthening CRVS systems by many low- and lower-middle income countries may be reduced due to restrictions imposed during COVID-19 and will require increased efforts after the pandemic.

The importance of maintaining civil registration during the pandemic has been underscored by the United Nations. The Committee on the Rights of the Child and the U.N. have called on states to protect the rights of children including maintaining “the provision of basic services for children including health care, water, sanitation and birth registration.” The United Nations Legal Identity Agenda Task Force has issued recommendations for civil registration authorities to ensure operational continuity during COVID-19 and allow for the continued production of comprehensive vital statistics, asserting: “Civil registration should be considered an ‘essential service’ mandated to continue operations during a pandemic.”

The onset and rapid spread of COVID-19 has proven traumatic to every country and sector of the globe. To ensure that vital events occurring during the pandemic are not permanently lost, it is critical that countries worldwide remove current barriers to civil registration and embrace CRVS systems as a core component of the COVID-19 response.

This piece is an output of the Bloomberg Philanthropies Data for Health Initiative. The views expressed are those of the authors, who have contributed in their personal capacities, and do not reflect the opinions or views of their agencies or of Bloomberg Philanthropies.

*COVID-19 and Civil Registration discussion group:

Don de Savigny, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute

Irina Dincu, Centre of Excellence for CRVS Systems

Anette Bayer Forsingdal, Centre of Excellence for CRVS Systems

Montasser Kamal, Centre of Excellence for CRVS Systems

Doris Ma Fat, World Health Organization

Fatima Marinho, Vital Strategies/Bloomberg Philanthropies Data for Health Initiative

Gloria Mathenge, The Pacific Community

Raj Gautam Mitra, United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

Jeff Montgomery, Registrar General, Department of Internal Affairs, New Zealand

Remy Mwamba, UNICEF

Alvin Onaka, State Registrar of Vital Statistics and Chief of the Office of Health Status Monitoring, Hawaii Department of Health

Tanja Brøndsted Sejersen, United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific

Lynn Sferrazza, Global Health Advocacy Incubator

Maletela Tuoane-Nkhasi, Global Financing Facility

Javier Vargas, Data for Health Coordinator, Peru

Benjamin Clapham, Vital Strategies/Bloomberg Philanthropies Data for Health Initiative