In the early 2000s, Senegal faced growing rates of tobacco use and related noncommunicable diseases. However, tobacco industry interference challenged the passage and implementation of comprehensive tobacco control policy in the country. Despite such challenges, in 2014 Senegal adopted a new comprehensive tobacco control law, which at the time was the strongest in the region. But how did advocates, public health leaders and policymakers achieve passage of such legislation? Recently, Vital Strategies released a case study and evaluation paper to explore that question.

Get Our Latest Public Health News

Join our email list and be the first to know about our public health news, publications and interviews with experts.

The publications look at how widespread social and traditional media campaigns, which were launched in Senegal in 2013, built momentum and public support for advancing tobacco control and catalyzed government action on a bill that had been languishing in Parliament for years. The campaigns were developed by Vital Strategies in partnership with Senegal’s Ministry of Health and the Ligue Sénégalaise Contre le Tabac (LISTAB), a Senegalese coalition of civil society organizations.

We asked Rebecca Perl, Vice President, Partnerships and Initiatives, to tell us more about why the campaigns were so successful in contributing to this legislative victory and what kind of lessons they offer for tobacco control advocates.

Why was it important to address the tobacco epidemic in Senegal?

At the time, Senegal was facing rising rates of tobacco use and related noncommunicable diseases. Among youth, the prevalence of smoking and secondhand smoke was especially concerning—in 2013, 14.9% of boys and 6.2% of girls aged 13 to 15 used tobacco products. Since then, youth tobacco use has declined, dropping to 11.6% for boys by 2020; though, there was a slight increase for girls (6.9%).

We knew that Senegal and other countries in sub-Saharan Africa were being targeted by the tobacco industry who saw, and still see, the region as a new frontier for customers, especially young customers, and interfere in countries’ efforts to regulate tobacco use. We needed to push back to drive tobacco control forward. Success in Senegal could then serve as an example, particularly for the Francophone Africa region.

Why did you launch the campaign when you did?

At the time of the campaign, which was 2013, there was strong, comprehensive tobacco control legislation in line with the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) that was drafted but was languishing in Senegal’s Parliament because of lack of political will and heavy industry interference. It included legislation on smoke-free areas; a ban on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship; increased taxes; and graphic health warnings required to cover 70% of cigarette packaging.

From 2011 to 2012, the Ligue Sénégalaise Contre le Tabac had been working hard to generate political will for tobacco control. This included securing support for a national tobacco control law from then-presidential candidate Macky Sall, who was later elected president. It was in 2013, with the Ministry of Health and the president’s support, that we joined forces with LISTAB to launch a strategy to build public and Parliamentary support for strengthening tobacco control. We had strong, committed advocates and political backing—the time was right.

Can you tell us about the different components of the campaign?

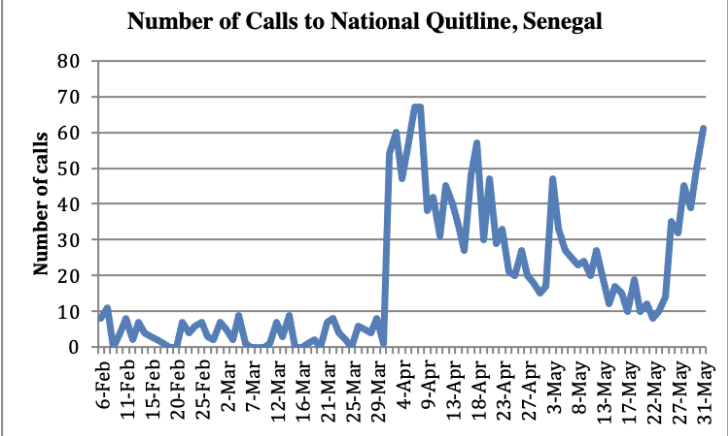

The campaign had both traditional media (television, radio etc.) and social media components in French and Wolof. We launched the traditional media campaign first using the public service announcement “Sponge.” “Sponge” graphically portrays the cancer-producing tar that accumulates in smokers’ lungs and urges smokers to quit and to call a national quitline for help doing so. This was the first-ever tobacco control campaign to be aired nationally over mass media in Senegal, so it was a very big step for the country. We reached a large portion of the population: 63% of people we spoke with in our study recalled the campaign. In addition, there was a large increase in calls to the quitline: 1,625 calls during the two-month campaign compared to the 236 calls that were received during the two months before the campaign.

Number of calls to national quitline before and after the traditional media campaign (billboards, television, radio), which ran April 1-May 31, 2013.

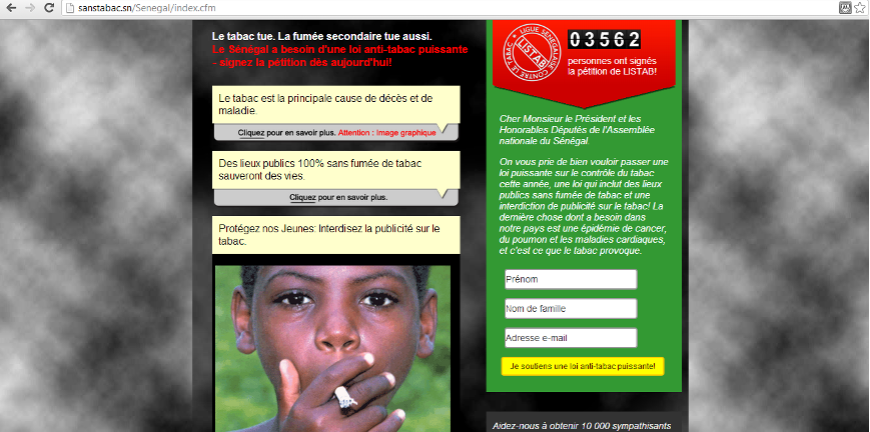

Following the traditional media campaign, we launched a social media initiative. At the time, more and more people in Senegal were using digital media. The campaign consisted of a Facebook page, directed advertising and a petition site where people signed on to express support for a stronger tobacco control law. In total, we had more than 8,000 people sign on to the petition and reached at least 3.5 million people online.

How did the campaign contribute to the passage of the legislation?

Causation is hard to prove with mass media campaigns, but we do know that shortly after the intense social media campaign, which had built upon the traditional media campaign, Senegal passed the tobacco control law that had been languishing for years. Given the timing, the social media campaign likely played an important role in elevating the issue to public consciousness and creating citizen advocates, enabling the legislation to pass. It’s a great example of how social media can be used in tandem with traditional media to create this kind of movement.

What factors do you think contributed to its success?

During the social media campaign, we were able to offer a range of social engagements, from very simple or low effort engagement, such as liking an anti-smoking image, to more committed actions, such as writing a letter to Parliament or attending a rally. This allowed online activities to serve as a funnel to concentrate offline pressure on the government through the media. I think this was one of the most successful aspects of the campaign.

Having a spokesperson for a campaign who is well-known and respected was also a good strategy. Dr. Abdou Aziz Kassé, who is a leading physician and president of the Ligue Sénégalaise Contre le Tabac, offered unwavering commitment to the cause and a willingness to serve as a central voice of the campaign for media and government stakeholders, which was undeniably at the core of our success.

What are the biggest takeaways for tobacco control advocates?

More and more people are on social media, especially young people. Across countries in Africa, Facebook is the network of choice and is embedded in day-to-day life. Social media is an increasingly powerful but underutilized tool for public health campaigns. Using social media, in addition to traditional media, allows us to reach different demographics and to interact and engage with supporters directly in ways that can then potentially draw their support offline.

This social media campaign in Senegal was one of our first. Today we work with partners on social media campaigns that run all year long in India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Mexico, for example. Campaigns have helped to increase taxes on tobacco in India, to contribute to cessation efforts in Indonesia and to pass legislation on national smoke-free public places in Mexico. This all goes to show that social media offers advocates immense opportunity to help advance tobacco control policy goals.

Read more about Vital Strategies’ work in tobacco control and follow us on Twitter: @VitalStrat