February is Black History Month—an annual celebration of Black culture and the achievements made by Black people in the U.S. and around the world. This month, we asked our staff to nominate stories of Black pioneers in health from the present and past who inspire them, whose bold first steps, leadership, research and inventions have saved countless lives and made the world a healthier and safer place.

The contributions that Black people have made to medical science and disease prevention are too often left out of history books. Many walked challenging paths tainted by prejudice and exclusion to contribute to scientific research and some of the greatest medical advances, often without ever receiving credit.

Get Our Latest Public Health News

Join our email list and be the first to know about our public health news, publications and interviews with experts.

This Black History Month and beyond, we honor Black leaders around the globe whose research, innovative thinking and activism continue to protect and save lives.

Mari Copeny

Activist and “Little Miss Flint”

At only 13 years old, Amariyanna “Mari” Copeny is an advocate and activist showing the world the power of young voices. In 2014, when Copeny’s hometown of Flint, Michigan, switched its water supply from Detroit’s system to the Flint River, residents began experiencing major water quality issues. The water was foul smelling and discolored, and it caused rashes, hair loss and itchy skin. Copeny sprang to action, writing a letter to President Obama about the water crisis. President Obama received the letter, visited the city and subsequently approved $100 million dollars in relief.

Now known as “Little Miss Flint,” Copeny continues to shed light on the dangers of environmental racism to communities around the United States, through her own experience in Flint. One of her biggest accomplishments is producing her own water filter with Hydroviv. Her water filters are shipped all over the country to those in need of clean drinking water.

Copeny also supports various social justice movements through her roles as National Youth Ambassador to the Women’s March on Washington and the National Climate March and has spoken twice at the March for Science.

Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett

Viral Immunologist

The 35-year-old viral immunologist and research fellow at the Vaccine Research Center of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is the lead scientist on the team that developed the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. Dr. Corbett also speaks publicly and works alongside Black leaders to help build trust in COVID-19 vaccines among Black people, who have been disproportionately hard hit by the pandemic but are mistrustful of medical institutions, given legacies of racist policies and practices.

Dr. Corbett’s lifelong passion for scientific research began when she was a high school sophomore and interned at a chemistry lab at the University of North Carolina, where she later earned her Ph.D. While there, she met scientists and researchers who furthered her passion in science. Now, in addition to her research at the Vaccine Research Center, where she has been since 2014, she spends much of her time mentoring young women, particularly young women of color, in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math.

Dr. John Nkengasong

Virologist and Director of Africa CDC

The Cameroonian virologist is the first director of the Africa Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC). At Africa CDC, Dr. Nkengasong leads the organization’s mission, supporting African nations in strengthening their public health systems. With Dr. Nkengasong’s expertise, Africa CDC and its partners have played a critical role in Africa’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic by distributing tests, strengthening capacity within countries and advancing the vaccine rollout.

Before his appointment to the Africa CDC, Dr. Nkengasong served as the Acting Deputy Principal Director of the Centre for Global Health for the U.S. CDC and the Associate Director of Laboratory Science and Chief of the International Laboratory Branch at the Division of Global HIV/AIDS and TB. In his earlier years, Dr. Nkengasong was working on HIV research as the Chief Virology at the Collaborating Centre for HIV/AIDs Diagnostics at the Department of Microbiology in the Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp.

Most recently during the COVID-19 pandemic, he was appointed as special envoy to the director-general of the World Health Organization. A champion of global health, Dr. Nkengasong continues to work with governments and international organizations, strengthening global cooperation and furthering research and innovation in public health.

Vanessa Nakate

Climate Justice Activist

Nakate grew up in Kampala, Uganda, a city heavily affected by climate change. Finding inspiration from the global “Fridays for Future” climate strikes, in January 2019 Nakate began to strike outside of Uganda’s Parliament. For many months she was the sole protestor, but soon she was joined by others. Nakate participated in over 60 Fridays for Future protests and then went on to found Youth for Future Africa and the Rise Up Movement. The Rise Up Movement helps amplify and strengthen the voices of African activists, especially those who are demanding climate action.

In 2020, along with other youth activists, Nakate helped publish a letter to participants at the World Economic Forum in Davos which included prominent companies, banks and government leaders, to take immediate climate action and stop investing in fossil fuels. When the Associated Press highlighted the young activists at the event, they cropped Nakate out from a photo, including only white activists. Nakate spoke out against the media’s erasure of African voices in a tweet stating “You erasing our voices won’t change anything. You erasing our stories won’t change anything.” The incident has strengthened Nakate’s commitment to highlighting the voices and work of African activists.

Dr. Camara Phyllis Jones

Physician and Epidemiologist

Dr. Jones is a family physician, epidemiologist and past president of the American Public Health Association. Dr. Jones has committed her career to naming, measuring and addressing the impacts of racism on the health and well-being of the United States. Through her work as a social epidemiologist and educator, she aims to broaden the health debate in the U.S. to include the social determinants of health, namely poverty, and the social determinants of equity, and racism. Dr. Jones’ allegories on race, racism and health outcomes, including her famed “Gardner’s Tale,” illuminate topics that are otherwise difficult for many people to understand or discuss. She hopes that her efforts to spread understanding of how racism affects health will initiate a national conversation on racism that will eventually lead to a National Campaign Against Racism.

Bobby Seale

Co-founder of the Black Panther Party and Public Health Advocate

Seale is best known as the cofounder of the Black Panther Party, but he was also a public health advocate working for improved health outcomes in Black communities. To increase access to health care for Black people and reduce disparities, Seale instructed all Black Panther Party chapters to open health care clinics called People’s Free Medical Clinics. There were clinics in 13 cities where volunteers dispensed basic medical care, as well as housing assistance and legal aid. The clinics also instituted a sickle cell anemia screening program to address the lack of attention and funding directed toward the disease that primarily affects people of African descent. These community efforts brought attention to the government’s inaction on the disease and led to the passage of the National Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act of 1972, which amped up testing and treatment. That same year, the Black Panther Party amended their Ten Point Program to include a vision to improve Black people’s health: “We want completely free health care for all Black and oppressed people.”

Dr. Joycelyn Elders

Pediatrician and Former U.S. Surgeon General

Dr. Elders was a pioneer in many ways. She was the first person in the state of Arkansas to become board-certified in pediatric endocrinology, and later the first Black person and second woman to head the U.S. Public Health Service when she was appointed surgeon general in 1993.

Dr. Elders grew up in a rural, segregated, poverty-stricken area of Arkansas where she and her seven younger siblings worked in cotton fields while pursuing their education at a segregated school they needed to travel 13 miles to attend. While studying at the all-Black liberal arts college Philander Smith in Little Rock, she heard a speech from Dr. Edith Irby Jones—the first Black person to attend the University of Arkansas Medical School. It was then that she decided to go to medical school.

As an endocrinologist, Dr. Elders combined her clinical practice with research that led her to study sexual behavior and to later advocate on behalf of adolescents. When she saw that young women with diabetes faced increased health risks if they became pregnant too young, she helped her patients to control their fertility and determine the safest time to start a family. Dr. Elders was appointed head of the Arkansas Department of Health in 1987. Under her leadership the state enacted a K-12 curriculum that included sex education, substance-use prevention, hygiene and programs to promote self-esteem. In addition, childhood immunizations nearly doubled and the state’s prenatal care program was expanded. Later, as surgeon general, she spearheaded efforts for sex education and drug legalization, refusing to water down her views in the face of backlash. She was pushed to resign after she argued that masturbation should be discussed in sex education. Dr. Elders was far ahead of her time; since then, many of her “controversial” ideas have become mainstream and there is better understanding of how they can promote health.

Dr. Charles Drew

Surgeon and Medical Researcher

Frequently called the “Father of the Blood Bank,” Dr. Drew was a surgeon and researcher who advanced the science of storing blood plasma for long periods of time and using them in transfusions.

Dr. Drew decided to pursue a medical degree after his sister died of tuberculosis. After graduating second in his class at McGill University Faculty of Medicine, he went on to became an instructor in pathology at Howard University School of Medicine. As the assistant professor of surgery and chief surgical resident at Freedmen’s Hospital at Howard University’s teaching hospital, Drew developed a method to separate plasma from blood, making it possible for it to be stored for a week, rather than only a few days. His discovery that transfusions could be performed with plasma alone widened the scope of who could be treated. Later, while at Columbia University in New York City, he founded and administered an early prototype program for blood storage and preservation. During World War II, this work became essential and saved thousands of lives.

During the war, Drew organized blood drives at New York City hospitals to gather plasma for use in British military hospitals. He was invited to join the American Red Cross as the first director of its blood bank, but resigned after less than a year after the Red Cross announced it would segregate the blood of white and Black donors. Drew returned to Howard University as chair of surgery to train the next generation of Black medical students.

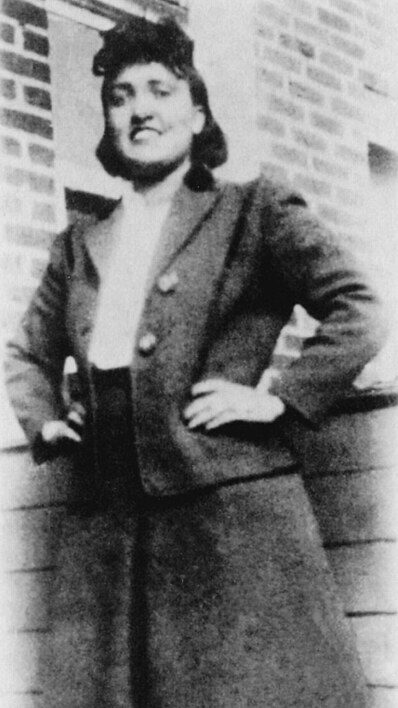

Henrietta Lacks

Changed the Face of Medical Science

In 1951, Henrietta Lacks was diagnosed with terminal cervical cancer and was treated by a doctor at Johns Hopkins Hospital, one of the few hospitals in the area that would treat Black patients. The doctor removed some of her cells without her consent. Lacks died from the illness shortly after her diagnosis. The doctor noticed that Henrietta’s cells were replicating rapidly and were essentially “immortal,” making them perfect for biological research. Her cells, which were code-named HeLa after her first and last names, have been used in countless research studies in the decades since. They facilitated the development of the polio and HPV vaccines, and were most recently used in research for vaccines against COVID-19. Although her cells were available globally for purchase online by researchers, Lacks’ family was not informed that her cells were being used for science, and they were not offered any kind of ownership or compensation.

Decades later, in 2013, the Lacks family entered into a HeLa Genome Data Use Agreement with the medical, scientific and bioethics communities, finally giving them a role in regulating the HeLa genome sequences and discoveries. To celebrate what would have been her 100th birthday in 2020, Lacks’ family launched a year-long outreach and education campaign, #HELA100, to share her story and honor the contributions she and her cells have made to medical research.

Vivien Thomas

Pioneer in Cardiac Surgery and Lab Supervisor

A pioneer in cardiac surgery, Thomas developed a procedure to treat the congenital heart defect that caused blue baby syndrome.

Thomas was born in Louisiana in 1910 and later moved to Nashville, Tennessee, with his family. In 1929, he enrolled as a premedical student at Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial College but was forced to drop out after the stock market crash that set off the Great Depression wiped out his life savings. In 1930, without having graduated, he took a position at Vanderbilt University as a laboratory assistant to surgeon Dr. Alfred Blalock, where he learned to perform complex surgical procedures. At the time, he was classified and paid as a janitor despite the fact that he was doing the work of a postdoctoral researcher.

Along with Blalock, Thomas began work in cardiovascular and cardiac surgery, which challenged medical taboos about operating on the heart. While at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Thomas co-created a method to correct a congenital heart defect, Tetralogy of Fallot, which is a primary cause of blue baby syndrome. During the now-famous first procedure on a human patient, Thomas was behind Blalock coaching him through the procedure. Thomas was not credited for his role in any of the studies that followed and had to wait decades to receive the recognition he deserved. The surgery Thomas developed has since saved the lives of thousands of children, correcting the lack of oxygen in the blood that turns a seemingly healthy pink baby a distressing shade of blue.

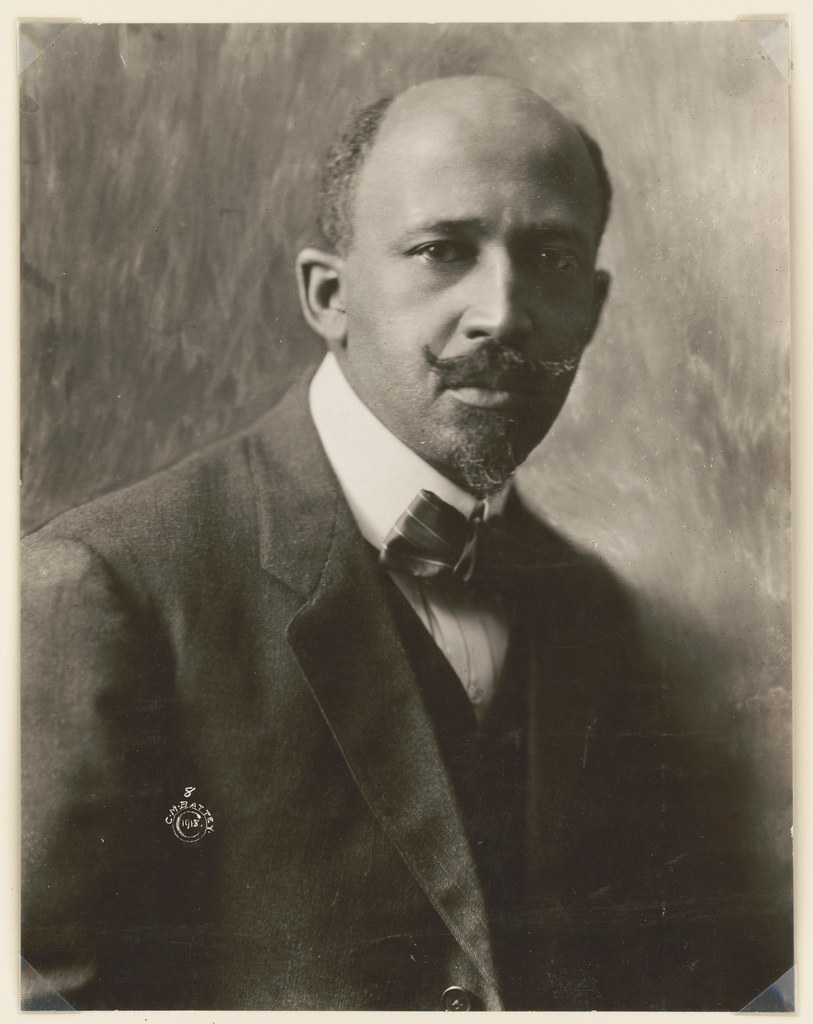

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (W.E.B. Du Bois)

Civil Rights Activist, Sociologist and Historian

A civil rights activist, Pan-Africanist, sociologist and historian, Du Bois was among the first to note that health disparities among Black populations when compared with white populations derived from social conditions rather than racial traits. He became one of the earliest critics of the racist pseudo-scientific beliefs popular in his time.

Du Bois was born in 1868 in Massachusetts. He later attended a historically black college, Fisk University, in Nashville. His experiences in Nashville of both Black culture and the effects of racism greatly affected him and shaped his work. Later, Du Bois went on to earn his master’s and doctoral degrees at Harvard University—becoming the first Black person to earn a Ph.D. at the university. He went on to complete the groundbreaking sociological study of a Black community in the U.S., “The Philadelphia Negro,” in which he demonstrated that racial differences in health reflect differences in social conditions and advancement. This research provided the backbone for what today are understood as social determinants of health, making him a forerunner of social epidemiology.

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler

First Black Woman Physician in U.S. and Early Medical Author

Dr. Crumpler was the first Black woman in the U.S. to earn an M.D. degree and among the first Black physicians to publish a medical book.

Born in Delaware in 1831, Crumpler likely decided to pursue medicine after watching one of her aunts spend much of her time caring for sick neighbors. In 1852, she moved to Massachusetts, where she worked as a nurse. She hadn’t had any formal training, since the first formal school for nursing did not open until 1873. In 1860, Dr. Crumpler was admitted to the New England Female Medical College. That year, there were only 300 women of the 54,543 physicians in the U.S., and none of them were Black. When she graduated four years later, she became the first Black woman in the U.S. to receive an M.D. degree.

After the Civil War, Dr. Crumpler moved to Richmond, Virginia, where she worked alongside other Black doctors in the Freedmen’s Bureau to care for people who were formerly enslaved, many of whom were refused treatment by white physicians. She later became one of the first Black physicians to publish a medical book, “A Book of Medical Discourses: In Two Parts,” which addressed children’s and women’s health.

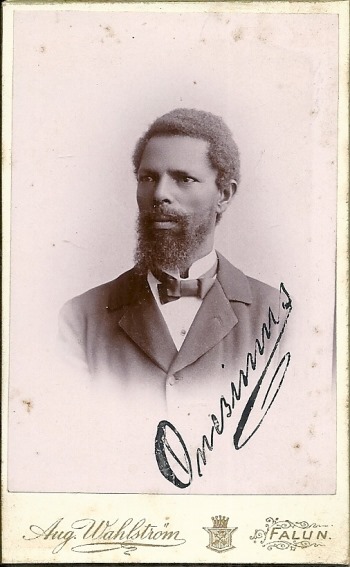

Onesimus

Introduced Inoculation to the American Colonies

Onesimus was a North African man who was kidnapped from his homeland and sold into slavery in Massachusetts. In the early eighteenth century, Massachusetts was being ravaged by epidemics of smallpox. When the man who had bought Onesimus, the Puritan minister Cotton Mather, asked him about a scar on his arm, Onesimus described the basics of smallpox inoculation—a practice that was already common in Asia and Africa. Mather was hesitant to believe Onesimus, wary of what he considered the “devilish rites” of Africans, but he shared the information with the doctor Zabdiel Boylston. Boylston inoculated his son and, without consent, two people who were enslaved, whose names are not known. Upon finding that the method (putting pus from an infected person into the broken skin of an uninfected person) could prevent severe disease, Mather and Boylston presented the technique to doctors who also refused to use a treatment from Africa—until they were faced with the deadliest smallpox outbreak in history. The inoculation proved to be effective in Boston and beyond; only one in every 48 inoculated patients succumbed to the disease compared with one in nine who were untreated. While Mather and Boylston went down in history, it was Onesimus’ wisdom that saved thousands of lives and it was he who brought inoculation to the American colonies.

Photo credits:

Mari Copeny / Hillel Steinberg

Dr. John Nkengasong / CDC Global

Vanessa Nakate / Paul Wamala Ssegujja

Dr. Camara Phyllis Jones / Aaron Shirley

Bobby Seale / Peizes

Henrietta Lacks / Oregon State University

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois / US Department of State

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler / Meserette Kentake

Onesimus / Aug Wahlström, Björn Alnebo